In late August, New York Times Magazine writer Steven Johnson authored an article titled “The Creative Apocalypse That Wasn’t.” The article made the point that, in spite of fears about the diminishment of creative sector jobs related to the sharing economy, those jobs are growing. The piece prompted a series of responses from a variety of organizations serving the arts, especially those associated with the music industry. Johnson, and the responding writers, helped illuminate how opportunities for file sharing, recording, downloading, and streaming online have impacted the music industry. Writers responding to the original article focused much of their attention on questioning the validity of the data Johnson used. This engaging dialogue has revealed some of the limitations inherent in data. While we often think of data as helping to clarify things and offering proof, sometimes data simply serves to confuse.

In the original New York Times Magazine article, Johnson outlined how the anticipated economic decline of individual music artists, which was predicted in the late ‘90s, was never realized. He used key examples of well-known individuals in the music industry to illustrate his point. He then drew on other creative sector disciplines to bolster his point. Though this sentiment of steady growth in the greater music industry may be a reality in some communities, it is not reflective of all communities nationally. There are a number of factors that make it a story that is challenging to tell through data.

Undercounting Informal Creative Endeavors

The original New York Times Magazine article and some of the follow-up posts agree that individual artists are finding increasingly dissperate paths to financial stability. However, in the new economy, many earning opportunities related to informal creative endeavors fly under the radar of national collection mechanisms for economic data. Add to this the fact that capturing all of the arts sector’s workers has never been an easy task, serious undercounting can occur. While no single national source captures all creative workers, some data sources are significantly more effective at capturing them than others.

The methods used by Economic Modeling Specialists International (EMSI), CVSuite™’s primary data provider, on average, capture 30-50% more creative sector workers* than other data providers. They do so by more effectively capturing self-employed and freelance workers. Use of EMSI data remediates some of the issues related to undercounting creative jobs that are found when researchers rely solely on the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages labor data.

Defining a Region’s Creative Economy

The accepted national-level data collection and reporting systems do not capture all creative activity. In spite of this, they remain the best available means to understand specific economic trends within a region. These systems–the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC), the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), and the National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities (NTEE)–are all used in the CVSuite™.

The issue with these systems is that the codes change over time. Thus, exactly what is being measured by the codes needs to be carefully considered when using these systems to measure a region’s creative economy. For example, in the New York Times Magazine piece, Johnson references NAICS industry code 711510: Independent artists, writers, and performers. The challenge with this code (which he notes in the article) is that it includes performers, which are sometimes creative performers and in other cases are athletes.

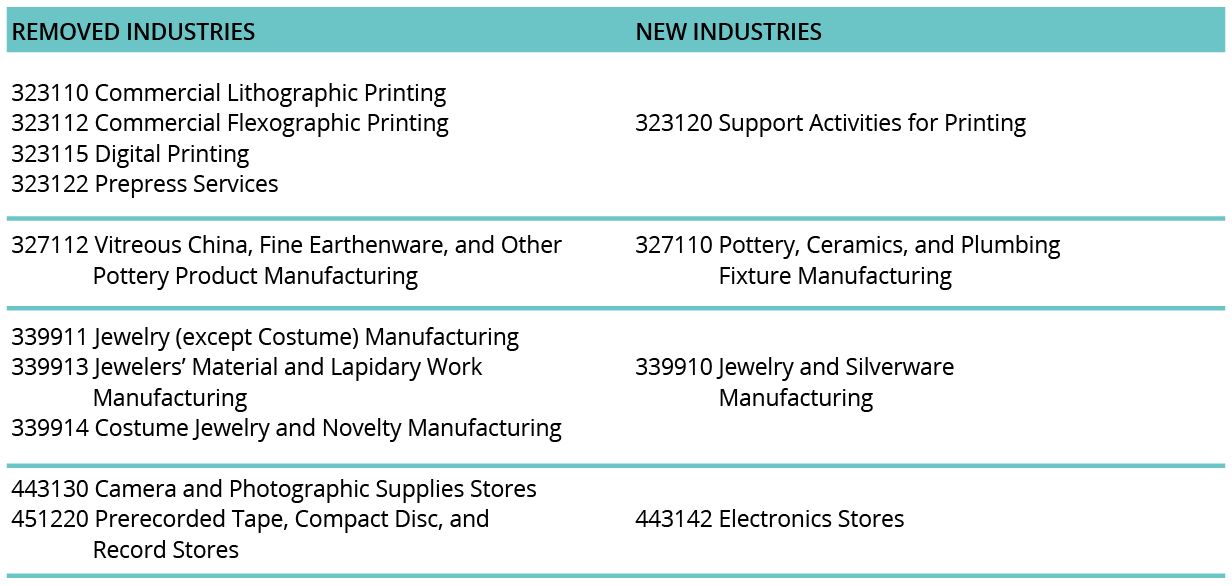

Other limitations relate to the vintage of the codes. NAICS code definitions are updated every five years. A recent change in NAICS codes that are used in the CVSuite™ combined two industries typically considered creative (photography stores and record/CD stores) into electronic stores (see chart CVSuite™: 2007 to 2012 NAICS code transition below). There are methods for isolating which part of this industry can be classified as creative; however, this example illustrates the level of complexity involved in choosing which codes to include in your research

CVSuite™ 2007 to 2012 NAICS Code Transition

Sales Data: Using Earnings vs. Sales

In the article, Johnson reviews sales revenues for NAICS industry code 71150: Independent artists, writers and performers. He highlights the finding that self-employed in this industry experienced a 60% increase in revenues between 2002 and 2012. This purported increase is suspect because industry revenue data are not the most accurate method for measuring economic impact in communities. In many instances, revenues captured in a region are expended in other regions for services not related to creative industries. Thus, although revenues may be attributed to a geographic area, if they are not spent there, they have limited economic impact. This CVSuite™ blog post outlines many of the issues related to the use of revenue data. In economic circles, earnings are viewed as a better indicator of economic impact. Earnings report the compensation of workers in a community and more of the earned income is expended in those communities.

How is the Region Defined?

Data is most actionable when it is community-specific. National level data, such as those reviewed in Johnson’s article, cast a very broad net merely providing a possible sentiment for the industries he reviews. Many times, when this sentiment is applied to the local level, it is inaccurate. Local trends need to be analyzed to capture the changes occurring at the grassroots level in specific communities. However, if data is viewed too narrowly, such as at census block or individual ZIP code level, the findings can be misleading. CVSuite™ data are best used when looking at areas with relatively dense populations that have a formalized economy.

The New York Times Magazine article is not totally inaccurate, but it is not totally accurate either. The article provides insight into what is occurring with individuals in the creative sector, but the data available to support the author’s argument need to be more carefully analyzed and some caveats need to be inserted. The article is rooted in data, but all data has a back story. Unless that back story is well understood, writings on the subject can raise more questions than they answer.

SOURCES:

- “Are Creators Really Thriving in the Digital Age? Doesn’t Look Like It.” Billboard. N.p., n.d. Web. 22 Sept. 2015.

- “The Creative Nonpocalypse” Cuepoint.Medium. N.p., 27 Aug. 2015. Web. 22 Sept. 2015.

- “The Data Journalism That Wasn’t.” Future of Music Coalition. N.p., n.d. Web. 22 Sept. 2015.

- “Can Data Capture the True Health of the Creative Economy?“ Johnson, Steven. The New York Times. The New York Times, 23 Aug. 2015. Web. 22 Sept. 2015.

- “The Creative Apocalypse That Wasn’t.“ Johnson, Steven. The New York Times. The New York Times, 22 Aug. 2015. Web. 22 Sept. 2015.

- “The New York Times Sells out Artists: Shallow Data Paints a Too-rosy Picture of “thriving” Creative Class in the Digital Age.“ Saloncom RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 22 Sept. 2015.

*Based on comparison to the Bureau of Labor Statistics QCEW data.

Comments are closed.